The caress of a stone in one’s pocket

Liza Maignan

if I eat a fruit I eat something past

I eat a seed I eat a tree I

eat anyone a rock the thigh

circular things

Laura Vazquez

Several green flags can point to the future characteristics of a relationship between two people, whether friendly, romantic, professional, temporary or eternal. One of these green flags is a shared appetite for all gustative forms. The first time Célie and I met, we sat in her garden and ate a kebab, which came from a fast-food restaurant that uses local products in their menus, earning them a best-in-town reputation. The second time we met was in Paris, where we shared plates of food with a bottle of fairly good value natural wine. The bar was tiny and seats were hard to get. Fortunately, Célie was an old friend of Julien’s, one of the owners, who secured us a table and welcomed us with generosity — a quality seldom seen in this type of Parisian establishment. There wasn’t any resident chef that week, but the large black-and-white posters adorning the back wall listed the names of all the chefs that had come to cook on the premises.

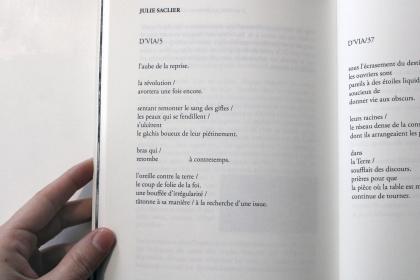

Célie Falières, Moins que demain, 2018, performance

Yesterday or tomorrow

I would’ve said yes to you

Yesterday or tomorrow

But not today.1

Two characters wearing masks made out of a soft, spongy material devour each other over the course of a song about lost love. A sourdough-tasting cannibalistic performance, in some ways reminiscent of the temporality of relationships: up to what point can we devour one another? Only after these brioche helmets have been completely eaten up are the faces revealed. Eating together is a choreography that unmasks. From chewing noises to fluids dribbling down fingers or from the corners of mouths, and from disgust to sensuousness, the language of eating and the language of desire converge in many points. I eat you up with my eyes.

Célie Falières, Courant Sagittal, 2018, performance, 30 stoneware enamelled plates, 25 metres of silkscreen tablecloth

I observe the changes in the faces of my fellow diners throughout each step of this nourishing ritual, with its savouring phases and various ways of sorting, ordering, ranking the food on the plate. There are those who combine, who dissect, who pick at it, who carefully adjust flavours, who sample each food type separately, those who savour, who wolf it down, and the plate moppers who leave no scraps. Looking at Célie’s two-serving dishes, I notice the sharing capacities of neighbouring diners. Each bite seems to reveal a flavour about ourselves, an interval during which our sense of conviviality is unveiled: there are the shameless spongers and those who never finish, leaving the leftover eaters free to empty their plate.

Célie Falières maps out territories and the elements that constitute them, just as she would organise the elements on her plate. She picks at them, gathers and gleans materials, vernacular forms, practices and customs from the territories she travels through serendipitously, wherever the journey might take her. In her studio, she inventories and classifies any and all possible ingredients: clay, plants, woods, fabrics, scraps, fungi, fossils, insects, shells, bones, natural elements or remnants of human activity. Her gestures translate materials in the same way one would translate the memory of a recipe by combining ingredients. She cooks up the flavours of a remembered elsewhere, enhances the taste of forgotten customs, nudges the natural towards the artificial, bends the reality of objects by shifting it from its nostalgic function to a narrative, imaginary or fantasised function.2 .

Célie Falières, Mégier, 2022, installation, exhibition view L’art de la rencontre #2, Maison des Métiers du Cuir, Grauhlet, France, photo Phœbé Meyer

Célie often quotes Virginia Woolf, who describes people as clumps of matter wandering aimlessly, with no other purpose but to take up space. And we even take up space after we die. I draw the Unnamed Arcana, card number thirteen, otherwise known as “Death”. It’s the right way up: a skeleton with a spine shaped like an ear of wheat reaps bodies and plants strewn across the blackened land. It could, among other things, herald a transformation. The reversible nature of the cards and the infinite number of possible interpretations are as countless as the strata that make up Célie Falières’ works. While some archaeo-acousticians have attempted to detect the muted murmurs of ancient daily life in the grooves of a terracotta jug, Célie, on the other hand, listens, observes and speculates on the fictional uses of objects, stories, skills and landscapes. Her gestures convey the merging of the materials she sculpts, weaves and assembles with her eyes. Célie’s practice delves into the ruins of history and seals the breaches of new fictions.

Célie Falières, Cavalcade, 2020, performance, photo Delphine Gatinois

A solitary cavalcade rings out to the rhythm of hooves beating the asphalt, like a funeral ritual. A figure wearing a black horse head mask single-handedly pulls a chariot made out of paper flowers, as is customary in the corso tradition — a parade of flowered chariots announcing the coming of spring. In times when culture has become a tool for far-right, patrimonial and conservative ideology, the route that this procession takes through an industrial desert implicitly traces the outlines of a territorial and rural context in which some of the paradoxes of popular folklores and traditions are embedded. In doing so, Célie makes it very clear that her practice, far from adopting a backward-looking position, is instead fuelled by forgotten techniques, which she repurposes to develop forms that interweave past and present times — forms that might withstand the identitarian and nationalist ideologies gaining traction in our cities and rural areas.

Translated by Lucy Pons

With the support of the Centre national des arts plastiques